But, again, what's one to do? There's no stopping The March Of Time, and I've always thought that technological interventions of a cosmetic sort are both unavailing and demeaning. But the mind is another thing entirely, or so one hopes. Ever fresher -- and never querulous -- is something to aim for.

'The Years O'

The days are drawing in,

A casual leaf falls.

They sag -- the heroic walls;

Bloomless the wrinkled skin

Your firm delusions filled.

What once was all to build

Now you shall underpin.

The day has fewer hours,

The hours have less to show

For what you toil at now

Than when long life was yours

To cut and come again,

To ride on a loose rein --

A youth's unbroken years.

Far back, through wastes of ennui

The child you were plods on,

Hero and simpleton

Of his own timeless story,

Yet sure that somewhere beyond

Mirage and shifting sand

A real self must be.

Is it a second childhood,

No wiser than the first,

That we so rage and thirst

For some unchangeable good?

Should not a wise man laugh

At desires that are only proof

Of slackening flesh and blood?

Faster though time will race

As the blood runs more slow,

Another force we know:

Fiercer through narrowing days

Leaps the impetuous jet,

And tossing a dancer's head

Taller it grows in grace.

C. Day Lewis, Pegasus and Other Poems (1957).

The title of the poem comes from a recurring refrain in Thomas Hardy's "During Wind and Rain." In the first stanza: "Ah, no; the years O!/How the sick leaves reel down in throngs!" And, in the third stanza: "Ah, no; the years O!/And the rotten rose is ript from the wall."

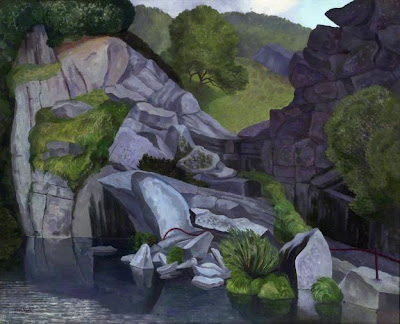

Norman Clark (1913-1992), "From an Upstairs Window" (c. 1969)

In fact, another poem of Hardy's provides a fine complement to Day Lewis's poem.

I Look Into My Glass

I look into my glass,

And view my wasting skin,

And say, 'Would God it came to pass

My heart had shrunk as thin!'

For then, I, undistrest

By hearts grown cold to me,

Could lonely wait my endless rest

With equanimity.

But Time, to make me grieve,

Part steals, lets part abide;

And shakes this fragile frame at eve

With throbbings of noontide.

Thomas Hardy, Wessex Poems and Other Verses (1898).

A classic Hardyesque mixed blessing: the flesh may fail, but the heart and the mind . . .

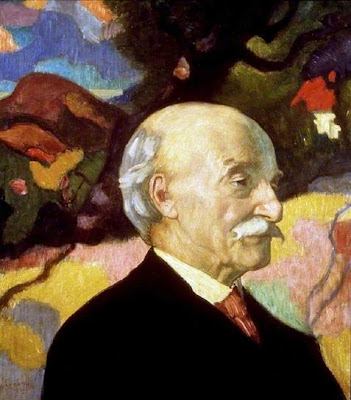

Norman Clark, "View over the Village of Hurstpierpoint"

Finally, the following poem provides, I think, an unillusioned yet hopeful way to approach these things.

The Rapids

Grieve must my heart. Age hastens by.

No longing can stay Time's torrent now.

Once would the sun in eastern sky

Pause on the solemn mountain's brow.

Rare flowers he still to bloom may bring,

But day approaches evening;

And ah, how swift their withering!

The birds, that used to sing, sang then

As if in an eternal day;

Ev'n sweeter yet their grace notes, when

Farewell . . . farewell is theirs to say.

Yet, as a thorn its drop of dew

Treasures in shadow, crystal clear,

All that I loved I love anew,

Now parting draweth near.

Walter de la Mare, The Burning-Glass and Other Poems (1945).

Norman Clark, "Flying Kites by a Gas Works near Bexhill"